Goring

READ LOCAL EDITIONTOP STORIES

Discover New Living at Henley Manor

Start the New Year by exploring a fresh approach to care, comfort and community at Hallmark Henley Manor. Families, friends and anyone curious about luxury care home living are warmly invited to pop in for their Taster Day on Saturday 24th January

Discover a New Way of Living at Henley Manor’s Taster Day

Start the New Year by exploring a fresh approach to care, comfort and community at Hallmark Henley Manor. Families, friends …

Continue reading "Discover a New Way of Living at Henley Manor’s Taster Day"

Meet the team at Freddie’s Pet Store

A community-focused Abingdon pet store inspired by one very special dog

Sly Dog Pure Fire: A Fiery Limited-Edition Winter Cocktail

Louis Goddard-Watts, co-founder of Sly Dog and Ginger Wing’s Jack Blumenthal have joined forces to bring you a fiery limited-edition …

Continue reading "Sly Dog Pure Fire: A Fiery Limited-Edition Winter Cocktail"

Oompah Oktoberfest

Tammy Nemeth invites you to enjoy an Oktoberfest evening on 31st October, starring Karl Bavarian Brass band in the beautiful & lively village of Ipsden near Wallingford

Ready for the new academic year?

Your go to revision specialists, to support your child with any tuition need.

Designs on your home

With over 30 years’ experience, you know you and your home are in good hands with Hazel Interiors

Tuck into Dracula!

Jigsaw Stage Productions invite you to tuck into Dracula in Steventon, Didcot, Challow & Grove between Halloween and Sunday, 9th November

Nine Lives Cat Rescue

A trio of feline-lovers are offering new hope thanks to Nine Lives Cat Rescue

No posts found

Recipes from The Skint Cook

We’re sharing a taste of inspiration from The Skint Cook, by Jamie Oliver’s Cookbook Challenge TV series finalist Ian Bursnall, out on 18th January

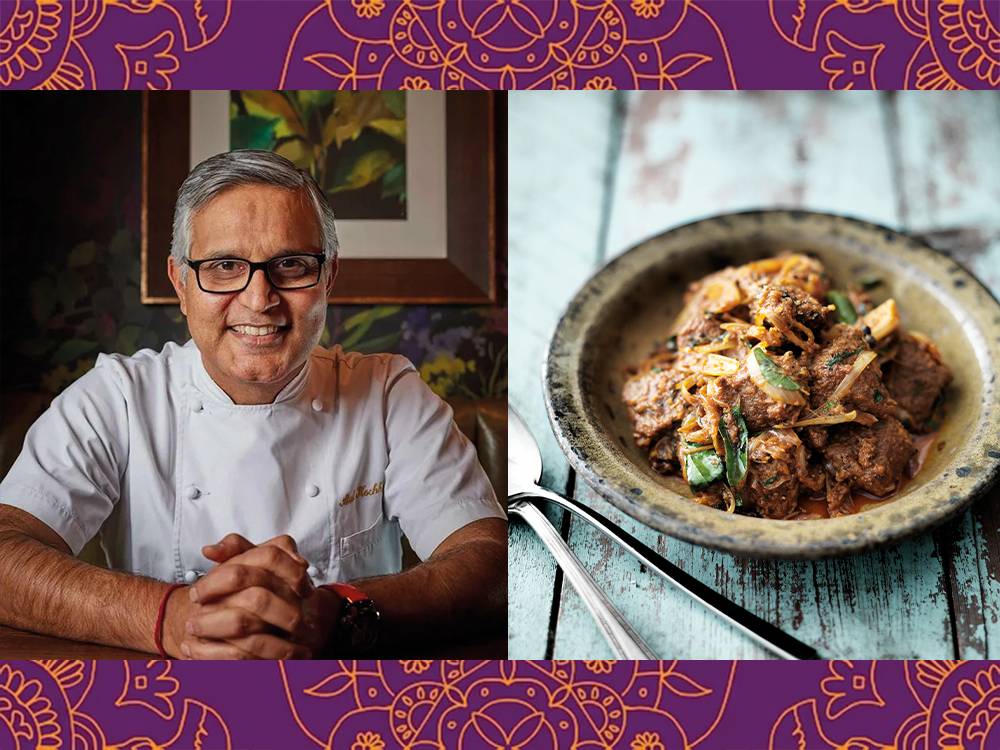

Diwali recipes & takeaway competition

Diwali recipes from Atul Kochhar and a chance to win a takeaway from one of his Bucks restaurant.

Sale e Pepe’s iconic Italian recipes

We share a taste of la dolce vita from Sale e Pepe which recently had a complete refurb ahead of its 50th anniversary.

Emily Roux’s packed lunch recipes

Chef Emily Roux and Lexus have rustled up some posh packed lunches to enjoy in the car or on your next road trip!

February recipes: Batch of the day!

Here’s a taste of Suzanne Mulholland’s The Batch Lady: Cooking on a Budget, out now, published by HarperCollins

Recipes: Life on the veg

Healthy, satisfying meals, that are quick and easy to prepare and come in on a tight budget are essential as we start 2023

November recipes: French Kiss

Cathy Gayner’s Recipes from Le Rouzet – An English Cook in France, is out now, in aid of Age Unlimited. Here’s a taster…

October recipes: Rice up your life!

We’ve teamed up with The Rice Association to offer you some seasonal inspiration to jazz up a store-cupboard ingredient.

September recipes: Good Mood Food

Ainsley Harriott shares two ideas from his newest cookbook.

Star Q&A with Dizzee Rascal

Liz Nicholls shares a chat with Dizzee Rascal MBE who headlines Party In The Paddock at Newbury Racecourse on Saturday, 17th August.

Star Q&A with Sharron Davies MBE

Liz Nicholls chats to Sharron Davies MBE as she looks forward to The Olympic Games – her 13th – starting later this month in Paris.

Q&A with music legend Chaka Khan

Liz Nicholls shares a chat with singer Chaka Khan who will star at Nocturne Live at Blenheim in June & Love Supreme festival in Sussex in July

Paloma Faith April music star Q&A

Musician Paloma Faith tells us about her new break-up album The Glorification of Sadness ahead of her UK tour which starts this month

Star Q&A: Timmy Mallett

Broadcaster, artist & dad Timmy Mallett, who turns 66 this month, tells Liz Nicholls about family, football, art and his new book Utterly Brilliant – My Life’s Journey

Prophet Sharing

The descendants of Abraham may have gone their separate ways, but now stand-up comedian friends Ashley Blaker and Imran Yusuf are joining forces.

Star Q&A with Dizzee Rascal

Liz Nicholls shares a chat with Dizzee Rascal MBE who headlines Party In The Paddock at Newbury Racecourse on Saturday, 17th August.

Star Q&A with Sharron Davies MBE

Liz Nicholls chats to Sharron Davies MBE as she looks forward to The Olympic Games – her 13th – starting later this month in Paris.

Q&A with music legend Chaka Khan

Liz Nicholls shares a chat with singer Chaka Khan who will star at Nocturne Live at Blenheim in June & Love Supreme festival in Sussex in July

No posts found

ABOUT US

Over the Years

2025

Round & About now have 31 editions reaching over 620,000 homes each month

22 employees, and over 600 businesses advertising each month

2019

The team won gold for Commercial Team of the Year and Regional Media Brand of the Year

at the British Media Awards 2019

2016

Round & About held

the first of two SO

Food Festivals

in Wallingford in September